Dutch Salmon's Country Sports Blog

Dutch blogged about hunting, fishing, the environment, books, country living and more. If you enjoy these stories, you might like Country Sports: The Rabid Pursuits of a Redneck Environmentalist, and Country Sports II: More Rabid Pursuits of a Redneck Environmentalist, collections of Dutch's best columns published bi-weekly in the Las Cruces Sun-News between 1999 and 2015. Both are available here on the website.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

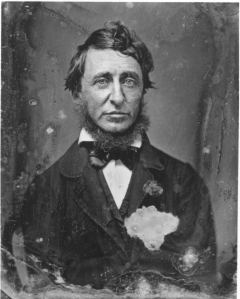

Maynard Hubbard (M.H. "Dutch") Salmon, II, (1945-2019) was an outdoor writer, publisher and founder of High-Lonesome Books, a small publishing company based in Silver City, New Mexico. He was a conservationist and environmental activist based in New Mexico as well as a fisherman, homesteader and well known coursing sighthound[1] breeder, trainer and hunter.

His father, John Pomeroy Salmon (29 December 1917 - 13 December 1966) fought in World War II with Edson's Raiders in the South Pacific[2][3]. His 4th great-grandfather was Moses Van Campen (21 January 1757 - 15 October 1859) who fought in the American Revolution, in particular, fighting the Indians in the frontier of western Pennsylvania.[4] His 2nd great-grandfather, John Niles Hubbard (27 August 1815 - 16 October 1897) wrote The Life and Times of Major Moses Van Campen about his grandfather, and Red Jacket and his People, 1750-1830, An Account of Sa-Go-Ye-Wat-Ha. His 2nd great-aunt was Lucy Maynard Salmon (27 July 1853 - 14 February 1927) who established the History Department at Vassar College.[5]

Biography

M.H. Dutch Salmon was born in Syracuse, NY, on March 30, 1945. Salmon attended high school at Nottingham High School in Syracuse, and The Winchendon School in Winchendon, Massachusetts, and after a short stint at the University of Michigan, he transferred and graduated with a bachelor of arts degree in English and History from Trinity University in San Antonio in 1967. Salmon taught school in the San Antonio area from 1968-1971 before moving to Minnesota to begin his life as an outdoorsman and writer. Salmon moved to southwest New Mexico in 1981 and began his lifelong work to preserve the free-flowing Gila[6][7][8][9][10]. Salmon died on March 10, 2019 in Las Cruces, New Mexico.[11] [12] [13] [14][15]

Recognitions and Awards

Salmon was a member of the New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission from 1985-1987; Founder and Chairman, Gila Conservation Coalition, 1984-2019[16]; Chairman, New Mexico Wilderness Coalition 1989-1995; Board Member, Quivira Coalition 2000-2006; Board Member, New Mexico Wildlife Federation 2005-2009; Board Member, New Mexico Water Dialogue, 2007; Board Member, Gila Resources Information Project 2004-2019, Member, New Mexico State Game & Fish Commission, 2005-2011 [17][18]. He received the Lifetime Conservation Award, Gila Natural History Symposium, 2008[19]; Lifetime Conservation Award, Gila Conservation Coalition, 2009[20]; Local Conservation Hero Award, Conservation Voters New Mexico, 2013; Luminaria Award[21], New Mexico Community Foundation, 2014.

Conservation/Environmentalism

Salmon moved to New Mexico in 1981. First to Catron County, and later to Grant County. In the spring of 1983, he took a hiking and canoe trip from the headwaters of the Gila River down to Safford, Arizona with a hound dog and a tom cat. In those days, the river was in danger of being dammed and he wanted to see it in its natural state for, perhaps, the last time.[22] The story of the trip turned into Salmon's best seller, Gila Descending, and launched his co-founding of the Gila Conservation Coalition[23] in 1984 and his lifelong quest to protect the free flow of the Gila and San Francisco Rivers and the wilderness characteristics of the Gila and Aldo Leopold Wilderness areas. He and the Gila Conservation Coalition were successful in defeating the Hooker and Conner dams and Mangas diversion in the 1980s and 1990s, closed the San Francisco River to motorized vehicle use, and also kept the East Fork of the Gila River closed to motorized vehicles. Since 2001, he was a leader in the fight against the diversion threat under the Arizona Water Settlements Act.

Bibliography

Books:

Non-Fiction:

Gazehounds & Coursing: The History, Art & Sport of Hunting with Sighthounds[24][25][26][27]

Gila Descending -- A Southwestern Journey[28][29]

Tales of the Chase -- Hound Dogs, Catfish, and other Pursuits Afield[30]

The Catfish as Metaphor -- A Fisherman's American Journey[31]

Country Sports – The Rabid Pursuits of a Redneck Environmentalist[32][33]

Gila Libre: The Story of New Mexico’s Last Wild River[34][35]

Country Sports II – More Rabid Pursuits of a Redneck Environmentalist[36][37]

Fiction: (Trilogy)

Home is the River[38][39]

Signal to Depart[40]

Forty Freedoms[41][42]

Magazines:

The American Hunter[43]

The American Saluki Association (ASA) Newsletter[44]

Bluetick Breeders & Coon Hunter's Association Blue Book[45]

Catfish In-Sider[46]

Discourse[47][48][49][50]

Earth Dog - Running Dog[51]

Field & Stream

Fins and Feathers[52][53][54]

The Fox & Coyote Hunter[55][56][57]

Fur-Fish-Game[58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66]

Game Country[67]

The Gazehound[68][69][70][71][72]

High Country News[73]

Hunting Dog[74][75][76][77][78][79]

In-Fisherman

Minnesota Sportsman[80]

Mother Earth News[81][82][83][84][85]

New Mexico Magazine[86][87][88][89][90][91][92]

New Mexico Wildlife Magazine[93][94][95][96][97][98][99][100][101][102][103][104][105]

The New Mexico Wildlife Federation’s Outdoor Reporter[106][107][108][109][110][111][112][113][114]

Outdoor Life[115]

The Performance Sighthound Journal[116][117]

Petersen's Hunting[118][119]

The Rabbit Hunter[120][121][122][123]

The Sighthound[124]

Sighthound Review[125][126][127][128][129][130]

Silver City Life[131]

Tally Ho[132][133]!.

Newspapers:

Albuquerque Journal (Correspondent (stringer), 1984-1988 (features and daily spot news for the State Page, Farm-Ranch Page, Outdoor Page and Business Page), Silver City Enterprise (Reporter, 1984-1987, features, spot news, outdoors column), Silver City Daily Press, (from 1997-1999, Outdoor Column -- "Country Sports" -- won 1st Place, Best Sports Column, New Mexico Press Association (Shaffer Award), 1998, and 1st place, Best Personal Column, New Mexico Press Women, 1998); Las Cruces Sun-News, (Outdoor Column -- “Country Sports” -- won “Best Column” award, New Mexico Associated Press, Columns, 1st Place-Division C, 1999, and Columns, 1st Place-Division A, 2000)[134], and again for the Silver City Daily Press and Independent from 2015 to 2019[135][136][137][138][139][140][141][142][143]. He was also the editor and publisher of the short-lived 1980s outdoors literary quarterly, Basin & Range[144][145][146].

Coursing

Salmon began his never-ending interest in gazehounds and coursing in south Texas in 1969. On moving to northwest Minnesota in 1971 he took open field coursing to a new level. To his Salukis 'Max' and ‘Sooner’ and greyhound 'Sally', he added a number of purebred Scottish Deerhounds which he described as his ‘favorite gazehound’[147]. His first, Shanid’s Germaine G came from the Shanid kennel in California in 1971[148], then in 1976 Ardkinglas Xpress (‘Pecos’) arrived from the famous Ardkinglas kennels in Scotland. In 1977 he added Crannoch's Lepus from Gerri Akman in Manitoba and organized hunts with a group of friends coursing snowshoe hare and fox over farm fields in Manitoba[149] and open field coursing white-tailed jackrabbits and Black-tailed jacks in North and South Dakota and Nebraska. In June 1977 Salmon traveled to Greenfield, MA to meet Miss Anastasia Noble who had bred his ‘Pecos’ and was judging the Scottish Deerhound Club of America National Specialty. The excitement of ‘Pecos’ reuniting with his breeder and the immediate bond between Miss Noble and Dutch, both strong believers in breed functionality, was a highlight at that show. This period in the American midwest was seminal in his understanding of the sport of open field coursing and he began work on the first edition of Gazehounds & Coursing: The History, Art & Sport of Hunting with Sighthounds. It filled a huge void in the literature on gazehounds and their function in the field[150]. A second edition, expanded and updated with two more decades of experience, followed in 1999 and still remains as the definitive on open field coursing with gazehounds.

After moving to New Mexico, Salmon crossbred various breeds for speed and endurance in pursuit of the desert Black-tailed jack and coyotes. He traded and sold his bloodline hounds to hunters across the country. He was a popular judge at coursing events throughout his life. He also raised a few trailing hounds and Jack Russell terriers mostly as co-hunters in helping to locate prey. Salmon founded the Desert Hare Classic in 1999[151] and the Desert Hare Pack Hunt in 2001[152].

References

- "Sighthounds". Wikipedia.

- Salmon, John P. "Raider Roster". Raider Roster.

- Alexander, Joseph H. (2001). Edson's Raiders. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. pp. 83, 90, 103, 117, 150, 152, 160, 211, 238, 268–270, 279, 325. ISBN 1557500207.

- "Moses Van Campen". Wikipedia.

- "Lucy Maynard Salmon". Wikipedia.

- Williams, Chris (7 January 2016). "Battle to Save New Mexico's Last Wild River". Truthout.org.

- Mahler, Richard (June 2009). "Redneck River Lover". desertexposure.com. Desert Exposure.

- Reed, Ollie (25 May 2015). "Gila Shows What A Natural River Should Look Like". Albuquerque Journal.

- Postel, Sandra (27 September 2011). "Still Wild and Free, New Mexico's Gila River is Again Under Threat". National Geographic.

- Yachnin, Jennifer (9 February 2015). "Greens gird for battle as N.M. floats plan to divert Gila River". E & E News.

- Plant, Geoffrey (12 March 2019). "Conservationist, author dead at 73". scdailypress.com. Silver City Daily Press and Independent.

- Murphy, Mary Alice (14 March 2019). "Salmon: M.H. "Dutch", 73, Silver City, NM". grantcountybeat.com. Grant County Beat.

- Neary, Ben (Spring 2019). "Dutch Salmon (pg 21-22)" (PDF). nmwildlife.org. New Mexico Wildlife - Outdoor Reporter.

- "M.H. Salmon Obituary". obits.syracuse.com. Syracuse Post Standard. 20 Mar 2019.

- Paskus, Laura (19 March 2019). "Defender of the Gila Passes On". New Mexico Political Report.

- "Conservation warrior, friend and colleague Dutch Salmon, 1945 – 2019". The Gila Conservation Coalition. 11 March 2019.

- Williams, Dan (25 February 2008). "Game Commission Elects New Officers". wildlife.state.nm.us. New Mexico Department of Game and Fish.

- Steele, Christine (18 March 2011). "More Commission Stuff". thenewmexicosportsman.com. The New Mexico Sportsman.

- Stevens, Donna (16 October 2008). "M.H. "Dutch" Salmon: Champion of the Gila (pg133)". gilasymposium.org. Natural History of the Gila Symposium.

- Murphy, Mary Alice (4 September 2012). "Gila River Festival Brunch in Honor or M.H. Dutch Salmon". Grant County Beat.

- "Meet New Mexico Community Foundation 2014 Luminarias". New Mexico Community Foundation. 9 July 2014.

- "Threats to the Gila River". Gila Conservation Coalition.

- Mahler, Richard (Spring 2014). "Gila Conservation Coalition Marks Its 30th Birthday". Gila Conservation Coalition.

- Salmon, M. H. (Maynard Hubbard), 1945- (1977). Gazehounds & coursing. St. Cloud, Minn.: North Star Press. ISBN 0878390243.

- Salmon, M. H. (Maynard Hubbard), 1945-2019 (1999). Gazehounds & Coursing: The History, Art and Sport of Hunting with Sighthounds. Silver City, N.M.: High-Lonesome Books. ISBN 0944383491. OCLC 44760288.

- Bell, Sally (April 1978). "Hounds in Print - Book Review". American Saluki Association (ASA) Newsletter: 66–68.

- Quigley, George R. (June 1978). "Gazehounds and Coursing by M.H. Salmon - Book Review". Hunting Dog. Volume 13, Number 6: 35.

- Salmon, M. H., 1945-2019 (2006). Gila Descending: A Southwestern Journey (4th ed.). Silver City, N.M.: High-Lonesome Books. ISBN 0944383203

- Duke, Raoul (9 August 2011). "Gila Descending by M.H. Salmon". bigbendchaat.com. Big Bend Chat.

- Salmon, M. H., 1945-2019 (1991). Tales of the Chase: Hound-dogs, Catfish, and Other Pursuits Afield (1st ed.). Silver City, N.M.: High-Lonesome Books. ISBN 0944383114.

- Salmon, M. H., 1945-2019 (1997). The Catfish as Metaphor: A Fisherman's American Journey (1st ed.). Silver City, N.M.: High-Lonesome Books. ISBN 0944383432.

- Salmon, M. H., 1945-2019 (2004). Country Sports: The Rabid Pursuits of a Redneck Environmentalist. Silver City, N.M.: High-Lonesome Books. ISBN 094438367X.

- Thompson, Fritz (July 3, 2011). "Nuggets dug up in a life outdoors (book review)". The Albuquerque Journal.

- Salmon, M. H., 1945-2019 (2008). ¡Gila Libre!: New Mexico's Last Wild River. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 9780826340825.

- Toth, Bill D. (Summer 2009). "Book Review". ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment. Oxford Academic.

- Salmon, M. H., 1945-2019 (2015). Country Sports II: More Rabid Pursuits of a Redneck Environmentalist. Silver City, N.M.: High-Lonesome Books. ISBN 9780944383810.

- Bodio, Steve (8 January 2016). "Country Sports II - Book Review". stephenbodio.blogspot.com. blogspot.com.

- Salmon, M. H., 1945-2019 (1989). Home is the River : [a novel] (1st ed.). San Lorenzo, N.M.: High-Lonesome Books. ISBN 0944383033.

- Salmon, M. H., 1945-2019 (1989). Home is the River : [a novel] (1st ed.). San Lorenzo, N.M.: High-Lonesome Books. ISBN 0944383033.

- Salmon, M. H., 1945-2019 (1995). Signal to Depart : A Novel (1st ed.). Silver City, N.M.: High-Lonesome Books. ISBN 0944383327.

- Salmon, M.H. (2010). "Forty Freedoms". High-Lonesome Books.

- Toth, Bill D. (Summer 2011). "Book Review". academic.oup.com. ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment.

- Salmon, M.H. (November 1980). "Beltrami Island State Forest: Few Hunters But Much to Hunt". The American Hunter. Volume 8, No. 11: 15, 50.

- Salmon, M.H. Dutch (October 1977). "Evaluating the Saluki As Gazelle Hound". The American Saiuki Association (ASA) Newsletter: 78–84.

- Salmon, M.H. (2018). "Ben Lilly Revisited". Bluetick Breeders & Coon Hunters Association 2018 Blue Book. 55th Edition: 52–55.

- Salmon, M.H. Dutch (January–March 2000). "Wilderness Catfish". Catfish In-Sider. Volume 3, No. 1: 22–25.

- Salmon, M.H. (Dutch) (1976). "Starting your Gazehound in the Field". Discourse. Vol. 3: 3–5.

- Salmon, M.H. (1977). "Some Thoughts From The Judge". Discourse. Vol. 4: 35–36.

- Salmon, M.H. (1982). "Starting Your Gazehound in the Field". Discourse. Vol. 9: 21–25.

- Salmon, Dutch (1983). "Coursing the King of the Hares". Discourse. Volume 10: 46–56.

- Salmon, M.H. Dutch (September 1999). "Back to the Future". Earth Dog - Running Dog. No. 86: 24–25.

- ↑Salmon, M. H. (June 1978). "Hunting With Sighthounds". Fins and Feathers. Vol. VII No. 6: 34–39.

- Salmon, M.H. (January 1980). "Hounds and the Brush Wolf". Fins and Feathers. Volume 9 Number 1: 12–16c.

- Salmon, M.H. (February 1980). "Showshoes - Your Best Access to Winter". Fins and Feathers. Volume 9 Number 2: 54–57.

- Salmon, M.H. Dutch (July 2001). "Coursing the Red Fox". The Fox & Coyote Hunter. Vol. 1 No. 4: 9–11.

- Salmon, M.H. Dutch (August 2001). "The Scenthound/Sighthound Combination". The Fox & Coyote Hunter. Vol. 1 No. 5: 12–19.

- Salmon, M.H. Dutch (September 2001). "First Annual Desert Hare Pack Hunt". The Fox & Coyote Hunter. Vol. 1 No. 6: 12–15.

- Salmon, M.H. (June 1974). "A Brief Look at the Gazehounds". Fur-Fish-Game. Volume 70 No. 6: 12–13, 42–43.

- Salmon, M.H. (February 1976). "Hounds for Coyotes". Fur-Fish-Game. Vol. 72 No. 2: 12–13, 22–24.

- Salmon, M.H. (February 1977). "High Sierra Hounds". Fur-Fish-Game. Vol. 73 No. 2: 8–9, 27–28.

- Salmon, M.H. (January 1980). "Hunting Fur with Hounds". Fur-Fish-Game. Vol. 76 No. 1: 12–13, 52–53.

- Salmon, M.H. (June 2005). "Longdog Revival: Thrill of the chase breeds a need for speed". Fur-Fish-Game. Volume 102 No. 6: 16–19.

- Salmon, M.H. (January 2011). "Crossbreeding for Do-It-All Coyote Hounds". Fur-Fish-Game. Volume 108 No. 1: 14–16.

- Salmon, M.H. (February 2017). "The Legend of Ben Lilly". Fur-Fish-Game. Volume 114 No. 2: 10–11, 56.

- Salmon, M.H. (October 2017). "Legendary Houndsman Montague Stevens". Fur-Fish-Game. Volume 114 No. 10: 28–31.

- Salmon, M.H. (November 2018). "Speed Thrills". Fur-Fish-Game. Volume 115 No. 11: 16–19.

- Salmon, M.H. (January–February 1989). "Home with the Hounds". Game Country. Volume 1, Issue 2: 89–93.

- Salmon, M.H. (May–June 1976). "American Coursing Hounds: Part II". The Gazehound. Vol. VI, No. 3: 146-.

- Salmon, M.H. (September–October 1976). "Starting Your Gazehounds in the Field". The Gazehound. Vol. VI, No. 5: 42–45.

- Salmon, M.H. (July–August 1977). "The Versatile Courser". The Gazehound. Vol. VII, No. 4: 154–156.

- Salmon, M.H. (September–October 1977). "The Hunter's Anticipation". The Gazehound. Vol. VII, No. 5: 150–151.

- Salmon, M.H. (May–June 1979). "Evaluating the Sighthound Breeds in the Field". The Gazehound. Vol. IX, No. 3: 38–44.

- Salmon, M.H. (9 November 2018). "A fishing rod stronger than war's dark legacy". hcn.org. High Country News.

- Salmon, M.H. (August 1972). "Greyhounds, Salukis and the Blacktail 'Jack'". Hunting Dog. Vol. 7 No. 8: 17–21.

- Salmon, M.H. (January 1973). ""Hot-Bloods," "Cold-Bloods," and "Staghounds"". Hunting Dog. Vol. 8 No. 1: 10–11, 45.

- Salmon, M.H. (June 1973). "Coursing the King of Hares". Hunting Dog: 12–14, 28, 52.

- Salmon, M.H. (August 1973). "Coursing Hounds and Cottontails". Hunting Dog. Vol. 8 No. 7: 13–14.

- Salmon, M.H. (August 1974). "Starting the Gazehound". Hunting Dog. Vol. 9 No. 8: 8–9, 57.

- Salmon, M.H. (December 1976). "Coursing The Red Fox". Hunting Dog. Volume 11, Number 12: 40–42.

- Salmon, M.H. (November–December 1979). "Longdogs". Minnesota Sportsman. Vol. 3 No. 6: 18–20.

- Salmon, M.H. (February–March 1998). "How to Run a Trotline". Mother Earth News. Issue No. 166: 60–63.

- Salmon, M.H. Dutch (1 April 1998). "Benefits of Raising Goats". Mother Earth News.

- Salmon, M.H. (May 1998). "Starting Right with Homestead Goats". Mother Earth News. Issue No. 167: 68–76.

- Salmon, M.H. "Dutch" (September 1998). "Books, Dogs, and Country Sports: A Tale of Independent Living". Mother Earth News. Issue No. 169: 50–55.

- Salmon, M.H. (November 1998). "A Real Thanksgiving Bird". Mother Earth News. Issue No. 170: 50–56.

- Salmon, M.H. (April 1982). "New Mexico's Swift Hounds - Tallyho the Garbage Bag!". New Mexico Magazine. Volume 60 Number 4: 22–23.

- Salmon, M.H. (July 1986). "Gila River Odyssey". New Mexico Magazine. Volume 64, Number 7: 37–42.

- Salmon, M.H. (March 1989). "Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument". New Mexico Magazine. Volume 67, Number 3: 12–13.

- Salmon, M.H. (September 1990). "Mountain men make last stand in Gila". New Mexico Magazine. Volume 68, Number 9: 44–51.

- Salmon, M.H. (January 2001). "Dust Bowl revisited". New Mexico Magazine. Volume 79, Number 1: 42–46.

- Salmon, M.H. (June 2003). "Gila's fabulous fishes". New Mexico Magazine. Volume 81, Number 6: 42–47.

- Salmon, M.H. Dutch (April 2004). "San Francisco Canyon: You'll Leave Your Heart Here". New Mexico Magazine. Volume 82, Number 4: 24–26.

- Salmon, Dutch (September–October 1981). "Running Rabbits". New Mexico Wildlife Magazine. Volume 26 Number 6: 17–20.

- Salmon, Dutch (January–February 1982). "Showshoeing". New Mexico Wildlife Magazine. Volume 27 Number 1: 25–29.

- Salmon, M.H. (Dutch) (September–October 1982). "Treeing the Tassel-Eared Tease". New Mexico Wildlife Magazine. Volume 27 Number 5: 14–17.

- Salmon, M.H. (May–June 1984). "The Hidden Gila". New Mexico Wildlife Magazine. Volume 29 Number 3: 2–5.

- Salmon, M.H. (May–June 1985). "Southwestern Bouillabaise". New Mexico Wildlife Magazine. Volume 30 Number 3: 26–29.

- Salmon, M.H. (May–June 1985). "River Bruisers". New Mexico Wildlife. Volume 31 Number 3: 22–25.

- Salmon, M.H. (January–February 1987). "To Hunt with Hounds!". New Mexico Wildlife. Volume 32 Number 1: 6–9.

- Salmon, M.H. (July–August 1987). "Bass Fishing Comes on Strong". New Mexico Wildlife. Volume 32, Number 4: 19–21.

- Salmon, M.H. (November–December 1987). "Handguns Prove a Challenge for Small Game". New Mexico Wildlife. Volume 32, Number 6: 26–28.

- Salmon, M.H. (January–February 1988). "Coyote Calls Can Be Deciphered". New Mexico Wildlife. Volume 33, Number 1: 26–28.

- Salmon, M.H. (March–April 1990). "Trotlining: True Sport?". New Mexico Wildlife. Volume 35, Number 2: 6–9.

- Salmon, M.H. Dutch (Summer 2008). "Native Gila trout inspire anglers old and new". New Mexico Wildlife: 8–9.

- Salmon, M.H. "Dutch" (Winter 2010). "A legacy of houndmen". New Mexico Wildlife. Volume 54, Number 4: 8–9.

- Salmon, Dutch (Fall 2013). "Every angler needs that 'personal place'". The New Mexico Wildlife Federation Outdoor Reporter: 7.

- Salmon, M.H. "Dutch" (Summer 2014). "Gila Wilderness: A legacy for sportsmen". The New Mexico Wildlife Federation Outdoor Reporter: 1, 4.

- Salmon, Dutch (Fall 2014). "Slot limits could lead to trophy bass, lengthy trout and big blues". The New Mexico Wildlife Federation Outdoor Reporter: 13.

- Salmon, Dutch (Summer 2015). "Eight questions for Dutch Salmon". New Mexico Wildlife Federation Outdoor Reporter: 14.

- Salmon, M.H. Dutch (Spring 2016). "Gila Descending, revisited". New Mexico Wildlife Federation Outdoor Reporter: 8–9.

- Salmon, M.H. Dutch. "Tales of Squirrels and Squirrel Dogs". New Mexico Wildlife Federation's Outdoor Reporter: 10–11.

- Salmon, M.H. Dutch (Spring 2018). "Gila Trout Inspires Anglers". New Mexico Wildlife Federation's Outdoor Reporter: 10–11.

- Salmon, Dutch (Fall 2018). "Slot Limits (pg 20-21)". New Mexico Wildlife. New Mexico Wildlife.

- Salmon, M.H. (Spring 2019). "Dog Days, Drought and Big Fish (pg 19-20)" (PDF). nmwildlifeorg. New Mexico Wildlife - Outdoor Reporter.

- Salmon, M.H. (June 1991). "Long Casts, Big Cats". Outdoor Life: 82.

- Salmon, M.H. Dutch (July–September 2007). "A Courser Looks at Jackrabbits". The Performance Sighthound Journal. Volume 4 Issue 3: 8–10.

- Salmon, M.H. Dutch (April–June 2011). "Coursing the King of Hares". The Performance Sighthound Journal. Volume 5, Issue 3: 8–9.

- Salmon, M.H. (September 1982). "The Southwest's Most Exotic Squirrel". Petersen's Hunting. Volume 9 Number 9: 56–58.

- Salmon, M.H. (May 1984). "Jackrabbits: America's Special Varmint". Petersen's Hunting. Volume 12, Number 5: 74–75, 89.

- Salmon, Dutch (June 2000). "Just One Jack: Blacktail Jackrabbit". The Rabbit Hunter. Vol. 14, No. 10: 20–26.

- Salmon, M.H. Dutch (February 2001). "Coursing Hounds and Cottontails". The Rabbit Hunter. Volume 15, No. 6: 30–36.

- Salmon, M.H. Dutch (November 2001). "Stags, Shags, and Scotch Deerhounds". The Rabbit Hunter. Volume 16 No. 3: 42–51.

- Salmon, M.H. Dutch (July 2002). "Off the Beaten Path: Hawks and Hares: A Pursuit for the Ages". The Rabbit Hunter. Volume 16 No. 11: 26–27.

- Salmon, M.H. (Dutch) (July–August 1982). "Hare on the Course". The Sighthound. Volume 2 Number 4.

- Salmon, M.H. (March–April 1999). "Country Sports: Rabbits are the Winner in Hare and Hound Competition". Sighthound Review: 4–6.

- Salmon, M.H. Dutch (May–July 1999). "First Annual Desert Hare Classic: A Study in Hounds and Sociology". Sighthound Review: 52–58.

- Salmon, M.H. Dutch (August–October 1999). "Breeding: An Excerpt from: Gazehounds & Coursing". Sighthound Review: 60–61.

- Salmon, Dutch (September–October 2000). "Whitetail Invitational". Sighthound Review: 86–88.

- Salmon, M.H. Dutch (May–June 2001). "First Annual Desert Hare Pack Hunt". Sighthound Review: 12–16.

- Salmon, M.H. Dutch (March–April 2002). "Stags, Shags, and Scotch Deerhound". Sighthound Review: 44–49.

- Salmon, Dutch (Winter 2008). "Fishing for Catfish". Silver City Life: 42.

- Salmon, Dutch (March–April 1980). "Hunting in the East". Tally Ho!. Volume 1, Number 2: 25.

- Salmon, M.H. "Dutch" (Autumn 1980). "Horseback With Hounds In Nebraska". Tally Ho!. Volume 1 Number 3: 18–20, 24, 27.

- "Writing the Southwest through History and Nonfiction". swwordfiesta.org. Southwest Festival of the Written Word. 15 August 2013.

- Salmon, M.H. (May 28 – June 3, 2015). "Archaic Wilderness: Anachronism and Necessary Antidote". The Silver City Daily Press and Independent. Vol. CXV, No. 238: 10–13.

- Salmon, M.H. (August 4–10, 2016). "Mountain Men of the Gila". The Silver City Daily Press and Independent. Vol. CXVII No. 35: 4–5.

- Salmon, M.H. (October 20–26, 2016). "Small Streams and Bass in Leopold's Wilderness". Silver City Daily Press and Independent. Vol. CXVII No. 99: 4–5.

- Salmon, M.H. (January 19–25, 2017). "Hoods In The Woods: A Wilderness Trek with Kids - Four-Legged and Two". Silver City Daily Press and Independent. Vol. CXVII No. 174: 4–5.

- Salmon, M.H. (March 23–29, 2017). "New Mexico's Last Grizzly". The Silver City Daily Press and Independent. Vol. CXVII No. 227: 4–5.

- Salmon, M.H. (October 26 – November 22, 2017). "A Mixed Bag, A Long Life". The Silver City Daily Press and Independent. Vol. CXVIII No, 102: 4–5.

- Salmon, M.H. (February 22 – March 28, 2018). "New (Fishing) Year's Resolutions: Angling for the Gila's Native Fish". The Silver City Daily Press and Independent. Vol. CXVIII No 187: 4–5.

- Salmon, M.H. (June 28 – July 25, 2018). "Robbed on the River". The Silver City Daily Press and Independent. Vol. CXIX, No. 4: 6–7.

- Salmon, M.H. (January 31 – February 27, 2019). "A Mule Speaks". The Silver City Daily Press and Independent. Vol. CXIX, No. 160: 9.

- Salmon, M.H. (July 1985). "Basin and Range". Basin and Range. Volume 1 Number 1: 1–56.

- Salmon, M.H. (August 1985). "Basin and Range". Basin and Range. Volume 1 Number 2: 1–56.

- Salmon, M.H. (September–October 1985). "Basin and Range". Basin and Range. Volume 1 Number 3: 1–52.

- Salmon, M.H. Dutch (1977). Gazehounds & Coursing. North Star Press. pp. 42–43. ISBN 0878390243.

- Salmon, M.H. Dutch (1977). Gazehounds & Coursing. North Star Press. p. 42. ISBN 0878390243.

- Salmon, M.H. (July–August 1977). "Footrace with a Fox". Claymore - Scottish Deerhound Club of America: 11–12.

- Salmon, M.H. Dutch (1977). Gazehounds & Coursing. North Star Press. p. 4. ISBN 0878390243.

- Salmon, M.H. Dutch (May–July 1999). "First Annual Desert Hare Classic: A Study in Hounds". Sighthound Review: 52–58.

- Salmon, M.H. Dutch (May–June 2001). "First Annual Desert Hare Pack Hunt". Sighthound Review: 12–16.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

White-out – A Close Call in Winter

November 6, 2015

Coming home from a jackrabbit hunt the other day, and passing through Deming, I tuned into Garrison Keillor and his “News from Lake Woebegone” segment of A Prairie Home Companion. Garrison Keillor said something like this: “On this day in November,” he intoned, “1975, three partridge hunters from the Twin Cities were caught in a blizzard up north in Lake of the Woods County and never made it out of the woods……” I was taken back some 40 years, for I lived in Lake of the Woods County at the time, and I too went hunting that day. I don’t recall any storm warnings on the radio re: weather. A congenital sleepy-eyed boy, maybe I just missed it. Or wasn’t paying attention. I should have been…

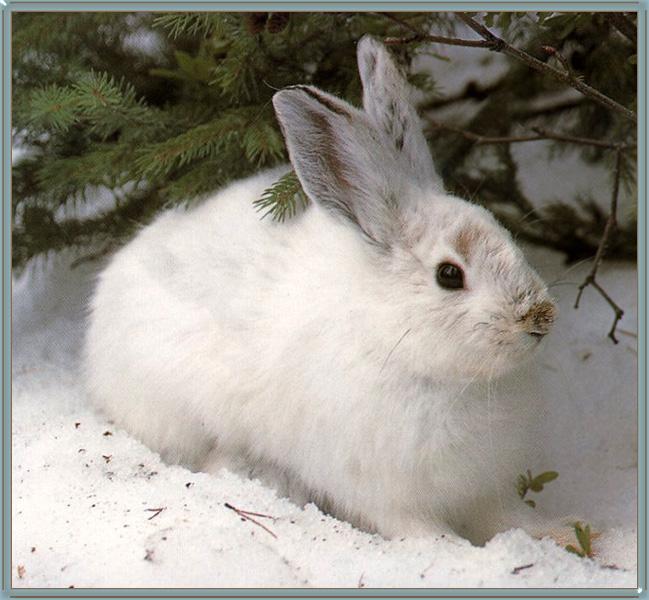

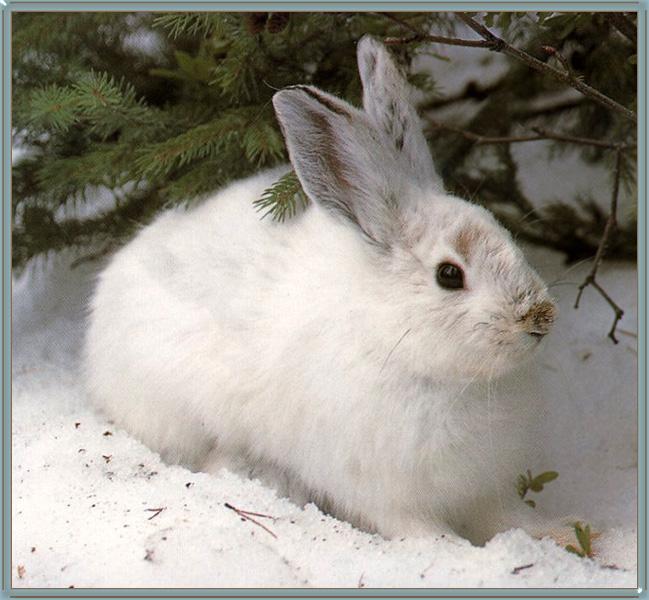

…It was abnormally warm that November morning; indeed I recall the entire fall as one long Indian summer. I’m sure I felt no need of gloves, ear-muffs, long johns and woolens, Sorel felt-insert boots, and other accoutrements of Minnesota winter garb. A pair of bib overalls and a light game jacket to carry the rabbits and ammunition seemed reasonable, considering the weather. This was going to be a lark; a morning afield with my two Bassett Hounds, Suzie and Phoebe, hunting for snowshoe hare. No snow on the ground and the hares were already turning an almost perfect white. After the first week of November, you don’t often find bare ground in Lake of the Woods County, Minnesota, hard on the Canadian border. What could possibly go wrong?

I was well armed, too: a Savage Model 24 with .22 magnum in the top barrel and twenty gauge full choke shooting #6 shot in the bottom. I drove to a remote section of the Beltrami State Forest – vast, flat, boreal woodlands – and turned loose the hounds.

We had a good hunt. Suzie, black, brown and white, a leggy Bassett, was of hunting stock and the leader; Phoebe, lemon and white, was more compact, but tireless and all heart and she had the better voice. Even with big, obvious white hares I proved I could miss my share of running rabbits driven hard by hound music. But I rolled three over in spite of myself – that was enough meat for all of us – and late morning I came out of the woods and sat on the tailgate, drinking coffee and waiting on the hounds. They were capable of running hares by the hour just for the fun of it but once she realized I was no longer in the woods backing her up, Suzie came to the same dirt road. She saw me and ran to the truck. I thought, “We could have some good running on the south side of the road here, too.” But Suzie sat there on the forest road and looked up at me like she was done. Odd! But I took her hint, opened the door, and she jumped in the cab of the truck.

Missing her hunting partner, Phoebe shortly came to the road as well. She, too, was oddly ready to quit. So I loaded her up; by this time a light snow had begun to fall and the wind had picked up. I poured more coffee and started a leisurely drive – about 15 miles – for home. With the dogs warming up the cab, steaming up the windows, and all of us happy from the hunt, it should have been a pleasant drive. But we almost didn’t make it.

By the time we were halfway there I was having trouble seeing the road. It was a mixture of falling snow and blowing snow, there was no definition between the road and the bar ditch, everything was white – a “white-out.” If I wasn’t already familiar with the road and the few turns required I would surely have driven into the ditch. As it was I crawled along in third gear and nearly missed my own driveway. Indeed, I passed it but saw the mailbox and backed up. Even then I had to get out and get a fix on the turn down the lane; there was a bar ditch there, too.

I got to the barn, got out, and noted that the temperature must have dropped 40 degrees from earlier in the day. Working without gloves, my hands started to sting and ache as I secured everything from the coming storm. The two bassetts thought this was all great sport; they played in the snow but stuck around till I was done and followed me into the house. I built a fire in the stove, made coffee and some lunch, cleaned three hares and knew I wouldn’t be going anywhere for the next few days.

In time the county snowplow opened up the county road and my driveway. I went to town and little by little caught on to how lucky I’d been. Garrison Keillor, some 30 years later, was right – two (or it may have been three), partridge hunters from southern Minnesota, hunting just a few miles from Suzie, Phoebe, and me, got caught in the same “white-out” while still in the woods. Without a compass, and totally disoriented by the storm, they never made it to the road. I doubt I would have fared much better if the hounds and I had not the luck to quit early that day and head for the barn. Indeed, if it wasn’t for Suzie, the clairvoyant bassett, I’d likely still be there, hunting the Elysian Fields on the south side of the road.

Note: This story will appear in the author’s next book – Country Sports – II: More Rabid Pursuits of a Redneck Environmentalist, due out before Christmas this year. Reach the author at: dutch@high-lonesome books.com

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

My Shot at the Gun Debate

October 6, 2015

Note: The recent mass-killing in Oregon has the gun debate on the front page once again. My thoughts on the issue have not changed, but because my “solution” is not to my knowledge being expressed elsewhere, I’m throwing it out there once more……MHS

Originally posted on January 12, 2013

“A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a Free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

Second Amendment to the Constitution of the United States

In my memory, the gun issue goes back to the assassination of John F. Kennedy, who, if you believe Lee Harvey Oswald did it, was killed with a mail-order gun. Guns have been a contentious political topic ever since, the issue currently at a war-like pitch due to the recent and almost unbelievable shooting-massacre at a Connecticut elementary school.

Only a fool consumed by self-delusion could think he might resolve this debate over gun violence with a partial page of (hopefully) well chosen words. Well, here goes!

First, I must acknowledge that I do not come at the issue from the middle of the road. I have been a gun owner for a long time and currently own a half-dozen guns, all used for hunting. I pay my yearly dues to the National Rifle Association (NRA), though I write to them from time to time when I view them as wrong-headed.

By rural New Mexico standards I suppose all this makes me a rather ordinary redneck, but hear me out — my suggestions are merely designed to work, not to please either the NRA or anti-gun lobbyists.

What set me off on this polemic was the re-reading of an old but still relevant article in the October 1999 issue of Harper’s Magazine. In a piece titled, “Your Constitution is Killing You,” Daniel Lazare summarizes his point: “The truth about the Second Amendment is something that liberals cannot bear to admit: The right wing is right. The amendment does confer an individual right to bear arms . . .”

Lazare arrives at this conclusion after nine pages of detailed scholarship that takes in the traditions of English Common Law, the social and political history of America’s Colonial period, and the writings of key Founding Fathers, including Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison. The crux of it is that at the time of the Continental Congress, a “well regulated Militia” and “the people” were one-and-the-same.

“If the framers were less than specific about the nature of a well-regulated militia,” Lazare writes, “it was because they didn’t feel they had to be. The idea of a popular militia as something synonymous with the people as a whole was so well understood in eighteenth century America that it went without saying . . ..”

Lazare believes that even liberal constitutional scholars are now more inclined to admit the truth about the rights of gun owners. He sees “a renaissance in Second Amendment studies” and “a remarkable about-face in how it is interpreted.”

He writes: “The purely `collectivist’ interpretation has been rejected across the board by liberals and conservatives as ahistorical and overly pat. The individualist interpretation . . . has been more or less vindicated.”

What makes Lazare’s consideration of the Second Amendment so interesting is that he is very much anti-gun. He is clearly in great fear of “the people” having the right to keep and bear arms and is looking for a way to abridge the liberty. That he comes to his conclusions reluctantly makes them all the more compelling.

Ultimately, Lazare offers his own solution to gun violence, one that is, in my view, extreme, wrong-headed, and untenable. Taking the Second Amendment at its word, and viewing modern gun violence with understandable horror, he believes we must amend or rewrite the Constitution to get rid of the individual right to keep and bear arms.

Politically, of course, this isn’t going to fly. The gun lobby is powerful and it has always been extremely difficult for anyone to change so much as a comma of the Constitution. And the Founding Fathers were prescient — they correctly saw guns as an element in protecting our individual and collective liberties. I believe they meant those liberties, and the Second Amendment in particular, to stand for all time.

All that said on behalf of gun ownership, we have got a terrific problem of gun violence on our hands and we must look beyond both the gun lobby, and the anti-gun lobby, to affect a solution. The first thing to recognize is that the Second Amendment does not confer an absolute right.

Nobody in the debate thinks convicted criminals or the mentally unsound should own a gun. We do not allow individuals to own bazookas, rocket launchers, or fully automatic weapons, and not even the NRA lobbys for their use outside the military.

In New Mexico, it is illegal to bring a firearm into a drinking establishment; nobody argues against this restriction.

So of course the “right” to keep and bear arms is limited, hopefully by reasonable restrictions. What’s reasonable?

Whenever government seeks to mold or correct human behavior by law, this principal should be followed: The maximum freedom possible for the law-abiding citizen; the maximum punishment possible for the criminals, violators and perpetrators.

Unfortunately, in our time, we tend to do just the opposite. We pass pervasive laws that oppress or hinder everyone, then go easy on the violators when they screw up. Only a very small percentage of gun owners ever abuse the privilege of owning a firearm. Nonetheless, the anti-gun lobby wants all gun owners to face a host of restrictions, such as outlawing cheap handguns, or all handguns, or semi-automatic rifles, or gun shows, or limiting the number of guns you can own, or can buy in a given period of time.

These regulations are not only ineffective, they infringe on law-abiding citizens. At the same time, we need to do a better job of keeping the bad guys away from guns, and instilling more responsible gun use in the populace.

The solution is not gun registration or a ban on certain guns, but the lawful licensing of gun owners on a national level.

The law, as I envision it, would allow any sane, law-abiding citizen to own, buy or sell, or use a variety of guns for any lawful purpose, once you get your gun license. Any adult gets the license (no local, state, or Federal entity could deny this) once they clear a background check, and pass a gun safety course.

Think of the sensible strictures and procedures that currently apply to anyone seeking a concealed carry permit, then apply something similar to the broader range of gun ownership and use. Anyone caught with a firearm and no license would be subject to prosecution. Likewise, any baseless or arbitrary denial of a permit would also be contrary to law, nationwide.

The licensing procedure, as I see it, would leave legal gun owners with more liberty, and a lot less hassle, than we have now, and would reassert the principal of the Second Amendment. But it would at the same time give the authorities a much better legal apparatus to weed out, or get at, the career criminals, crazed teenagers, mentally unstable adults, and others that shouldn’t own a gun. And if every gun owner had to take the safety course, there would be a lot fewer accidents.

By licensing, I suggest a gun rights law, and a gun control law, all in one package.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Fishing for Buffalo

September 18, 2015

Leave it to Bob Brady of Silver City to teach me something new about the outdoors. Fishing off the bank last week in Caballo Reservoir, he caught a 12 lb., 3 oz. smallmouth buffalo fish. I wasn’t with him but he sent the picture to prove it and based on my experience with the species, that’s what it was alright. I’ve fished Caballo and Elephant Butte on and off since 1982 and It was news to me that we had the smallmouth buffalo in our two big local lakes and adjacent Rio Grande.

“Oh yes, they’re really quite common,” said Kevin of New Mexico Game & Fish in Las Cruces, “and not only that, they’re native to the Rio Grande system. But few people fish for them, or know how to catch ’em.”

Well, I’m no expert, but I have caught a few from years ago in Texas, from the Trinty, Neches, and Nueces Rivers, and here’s what I’ve learned about them as regards natural history and sport.

The smallmouth buffalo (and it’s relatives bigmouth and black buffalo) is a member of the sucker family. They look a lot like a carp with added buffalo hump but lack the barbels at the mouth. They’ll average two to about 15 lbs. but like the carp have the potential to get much bigger. A yu-tube video had a guy along some southern river battle a 30 pounder to the net. And a Texas Parks and Wildlife report said the state record smallmouth buffalo on rod and reel is 82 lbs. ; the biggest on trotline is 97 lbs.! Further, more than one Internet site said the smallmouth buffalo is the number one commercial fresh water food fish in North America. And I just remembered I once caught one (1970s) from the Red River of the North in Manitoba; that’s a rangy fish.

Bob Brady said he caught his at night on a nightcrawler while fishing for catfish. I’d fish for buffalo same as I fish for carp — chum out some Green Giant canned corn, then put two kernals on a #8 hook and with a sliding sinker put it out there amongst the chum with the line on free spool.

I’d prepare them for tablefare same as I do a carp — filet a slab off the rib cage on either side and cut out any red or oily meat. There will still be floating bones but you solve that by grinding up the meat like hamburger, then add seasoned bread crumbs for body and flavor and either fry as fish patties or bake as a fish loaf.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Farm Ponds and Fabulous Fishes

September 10, 2015

In the hands of wordsmith Henry Thoreau, an every-day pond and it’s fish become quite “fabulous.” This short tale, and others like it, is from my up-coming COUNTRY SPORTS – II, scheduled for publication November, 2015. — MHS

At first glance, to a fisherman, a pond might seem less impressive, and less productive of fish, than a lake. And more prosaic than a stream or river. On second glance, that may just depend upon the pond.

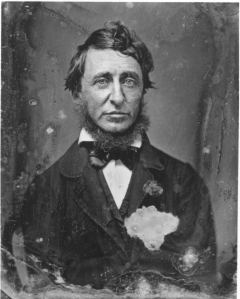

First I guess we’ll have to take a stand and distinguish between a pond and a lake. I was going to say something like 60 surface acres seems a good separation and after looking around I’m thinking that’s pretty close to good. Henry Thoreau after all called his favorite water “Walden Pond”; he wrote that it was 61 surface acres in size, and it’s a good thing for him he called it a pond because “Walden Lake” doesn’t quite get it. Walden Pond is cool; Walden Lake? Golly, I don’t know if Henry would have ever found a publisher! Anyway, I’m here to say that for this story a pond is a small lake of less than 100 acres whose waters are essentially still rather than flowing like a stream.

In a chapter in Walden called “Higher Laws’, Henry takes on the subject of hunting, meat eating, animal rights, etc., and while somewhat ambivalent throughout the discussion, he has clearly got the vapors about killing and/or eating animals, the main objection being that hard labor caused him to have to eat “coarsely.” The coarse part of the meal, of course, being the flesh of animals. But for Henry, animals apparently were on some other level than fish.

“Fishing,” he confesses, “still recommends itself to me.” And the best fish in Walden Pond he describes like this: “I am always surprised by their rare beauty, as if they were fabulous fishes……it is a wonder that they are caught here, that in this deep and capacious spring…..this great gold and emerald fish swims…..Easily, with a few convulsive quirks, they give up their watery ghosts …..like a mortal translated before his time to the thin air of heaven.”

Written by a true transcendentalist; keep the meat, free the spirits; no catch-and-release angler was this bard of Concord! And the great gold and emerald fish native to this “deep and capacious spring” is not the largemouth or smallmouth bass, though they too can in some waters sport “great gold and emerald” colors, but the chain pickerel, a lowly species, as generally conceded by today’s angler. I can’t recall that I’ve ever seen a pickerel story written up as a feature in one of the Hook-and-Bullet magazines; no Pickerel on the Fly on your bookshelf or mine. Yet with Henry Thoreau as companion and scribe, fishing in a farm pond named Walden, this still-water pickerel is a rare pleasure and stimulates a precious literary legacy.

I’ve read Henry’s Walden Pond book early in life and again, later, in college, and every few years even now. But I’ve never fished its waters. My first experience fishing someplace like it was the Vanderkamp Pond in upstate New York, north of Oneida Lake, on the fringe of the remote Tug Hill Plateau. My cousin Hank was part of the family that owned The Vanderkamp; several hundred acres plus the pond that I’m guessing was close to 100 acres itself.

Whatever the size it was full of a very game fish that jumped, some weighing several pounds, and because it was a private pond the fish were seldom fished and vulnerable even to young teens who were just winging it on this new species – largemouth bass. Our weapon of choice was the Hula Popper.

I wonder if they still make that plug? A short, fat cigar stub in size with a hairy hula skirt round the middle; you’d throw it out there on the edge of the cattails, give it a “pop,” then see how much patience you had as you waited for a big largemouth to blast it off the surface. Fewer pops was generally better but the temptation was great to keep it moving if you didn’t get a hit right away and then the popper was soon off the habitat and a bass would rarely venture beyond his cover.

We got good at “edging” that cover though and caught some beauties, some real bruisers, in spite of ourselves, and the fishing was invariably good ‘cause me and Hank were the only ones using it……..the name Vanderkamp soon became Abandoned-kamp in our lexicon and remains so today though our time there is long past. Anyway, it was quite a pond.

We have a number of ponds in southwest New Mexico, like Bill Evans, Bear Canyon, and Lake Roberts. These sometimes produce well, and sometimes not, but they’re likely crowded on the week end. So I’m going to write about a little 15-acre pond I know that’s private and nameless and rimmed with big shade trees. Despite its small size it’s got some nice largemouth, big bluegill, and the odd warmouth bass.

The warmouth bass looks a lot like a rock bass but is prettier – reddish-brown streaks along the lateral line, yellow belly and orange spots on the dorsal fine — and is actually a member of the sunfish family. They get up to 2 lbs. or a bit more and the one I caught on my last trip to this small water was over a pound with a lot of “pull.” What they do when hooked is get that wide body broadside to the angler and the direction of the line and “fight big.” I was using a 4-weight rod and started with a Pistol Pete and it was too heavy for the leader. So I switched to a smallish wooly bugger and my landings improved though I think I only landed four fish, the warmouth the biggest.

Stephen O’Day and son Bud used spinning outfits and easily caught more than me and it was a lovely day and I got a bang out of that warmouth bass on a fly. I hadn’t caught one of those in years, and this pretty fish and place and day offered up a good example of farm pond fishing. Henry caught it just right: “I am always surprised by their rare beauty,” he said, “as if they were fabulous fishes.”

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

B. Traven's Wilderness

August 18, 2015

Many read B. Traven as a proletarian and adventure writer; few as a wilderness lover with a conservation ethic. We should take another look. The following essay appeared in my 2004 book Country Sports. — MHS

Howard: We’ve wounded this mountain. It’s our duty to close her wounds. It’s the least we can do to show our gratitude for all the wealth she’s given us. If you guys don’t want to help me, I’ll do it alone.

Bob Curtin: You talk about that mountain like it was a real woman.

Fred C. Dobbs: She’s been a lot better to me than any woman I ever knew. Keep your shirt on, old-timer. Sure, I’ll help ya.

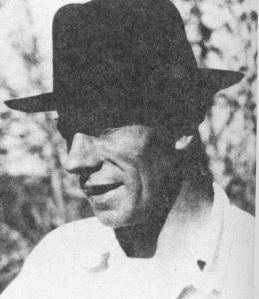

The lure of the wild may come unbidden. And often a mentor―or several of them―provides an introduction to the natural world that is practical, or inspirational, or both. I count my father, Theodore Roosevelt and Aldo Leopold as influences on my outdoor pursuits; they helped get me there, and taught me the joy and the respect. And there was one other man who drew me off the beaten path, who reached me as a writer as did Roosevelt and Leopold, though he was hardly an outdoorsman at all.

It was the 1960s, colleges were in turmoil over “movements”―anti-war, feminism, the sexual revolution. The sexual revolution had my attention, but otherwise on the enormous campus where I found myself I felt like a man (or more precisely a freshman) out of time. Misplaced and homesick, I took note when the campus art cinema advertised a showing of “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre.” I thought, perhaps a “Western” will offer some reprieve.

This was no ordinary Western. As Dobbs (Humphrey Bogart), Curtin (Tim Holt) and the Old Man (Walter Huston) left the evils of urban Mexico for the wilds of the Sierra Madre I envisioned my own release from pain. The film offered splendid realism, made the more so by the screening in understated black and white. Everything was “on location” in Mexico. The Mexicans spoke Spanish (not the silly accented English so often heard in films), and the burros were packed as if the search for gold would take months. Which it did, while Dobbs, Curtin, and the Old Man looked increasingly scruffy, dirty, and suspicious as they considered whether they could trust each other with all that loot. And through it all was the backdrop of the Mexican wilderness. A misplaced freshman was ready to run to the hills.

In the end of course Dobbs loses his life to greed. Curtin leaves in search of a woman and a peach orchard in Georgia. The Old Man returns to the mountains to live with Indians who know happiness with few material wants. And the gold dust blows away in the wind.

Outside the theater, and back to reality, I didn’t run. Not right then, anyway. But I did make it a point to read the book upon which director John Huston based his film. More complex and complete than the film, and less tightly woven, it was written by a strange bird named B. Traven. To the end of his life, not even his several wives knew who he was.

B. Traven was the great mystery man of 20th century literature, hiding from the age of 25 behind a dizzying assortment of aliases, pen names and created personas, all carefully applied by the writer to confuse the press and keep the public (and sometimes the authorities) out of his life.

“Traven is not important; Traven’s works are important,” he proclaimed time and again from various furtive locales in Mexico. He did protest too much; ironically, the mystery of B. Traven always overshadowed his books. This mystery was essentially solved in 1980 with the publication of The Secret of the Sierra Madre by British journalist Will Wyatt. In summary, it is now known that B. Traven was a German (not an American as he always claimed), born Otto Feige in that country in 1882. Feige disappears about 1904, but the same man reappears in 1907 as . . . Ret Marut, actor, anarchist and radical journalist. In 1922 Marut narrowly escapes a firing squad during a right wing coup in Bavaria, sails the seas in search of a country for a couple of years, arriving finally in Mexico in 1924 as . . . T. Torsvan. In 1925 the writer B. Traven appears in print―though never in public―with the first of 12 novels. Meanwhile Torsvan fronts for Traven until 1946 when he, too, disappears, only to be replaced by . . . Hal Croves, who dies in Mexico, denying to the end he’s Traven, in 1969. Got it?

Anyway, Feige, Marut, Torsvan, Traven, Croves were all the same man. This man lived in cities most of his life. Yet in tracing Traven’s literary biography, we find that his principal inspiration came from wilderness.

As Ret Marut, Traven was a prolific journalist and polemicist in Germany. But he wrote nothing of lasting value and had his career ended there he would be unknown today. Shortly after arriving in Tampico in 1924 however, he joined a government agricultural expedition as scribe and photographer. For the better part of the next year he toiled with the expedition in the Mexican wilds, mostly in the state of Chiapas, assessing agricultural possibilities, natural history, and the lives and lifeways of the native peoples. For the rest of his life Traven would live in Tampico, or Acapulco, or Mexico City. His ramblings off the beaten path were quickly done. But the Mexican wilderness transformed his creative spirit; from his brief sojourn in the wilds came The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, March to the Monteria, The Rebellion of the Hanged, The Bridge in the Jungle and almost all the other novels for which he is known.

I’ve read The Treasure of the Sierra Madre several times. And every few years I plug John Huston’s film into the VCR. I know all the memorable scenes, all the good lines, by heart. The quest for gold, the lure of the wild, the scene of tired men and loaded burros breaking trail continues to inspire. When I go into the wilderness of the Gila, I backpack, or use pack goats, to carry the goods. But there’s no doubt that Dobbs, Curtin, the Old Man and those burros showed me the way. My material wants are few in the wilderness, and the irony of gold that blew away in the wind all the more clear. From my time in the wilderness, I’ve found stimulus to write some books of my own.

B. Traven wrote: “The treasure you do not think it worth the pain and trouble to find, that is the real treasure you have been searching for all your life. The gold you seek lies just beyond the rim of that hill yonder.”

It seems the gold is always just beyond the rim of that hill yonder; and even if we found it, it would probably belong to the government. But it’s still possible to strike it rich off the beaten path.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

ISC Fudges the Facts

August 7, 2015

A Joint Powers Agreement (JPA) has been signed by some 15 governing entities, or quasi-governing entities, seeking the divert some 14,000 af of water from the Gila River in southwest New Mexico. Notable by it absence from this list is Silver City, which voted unanimously in June not to join in the JPA, realizing that conservation and modest development of prodigious ground water reserves in the Mimbres Basin would secure a comfortable water future for the town at a fraction of the cost of the diversion. The New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission (ISC), principal proponent of the massive dam/diversion of the state’s last free flowing river under the Arizona Water Settlements Act (AWSA) wasn’t taking any chances when it came Deming’s turn to vote on membership in the JPA. What did the ISC/Deming do?

First, they rigged the meeting of the city council so there would be no public comment period, except for that public comment period provided to the ISC, and thus there could be not only no presentation by opponents of the dam but as well no cross examination of the ISC point of view and faulty data. This is where the ISC had free reign to fudge the facts, principally concerning the costs of the project and the amount of water available for beneficial use.

Craig Roepke, Deputy Director of the ISC, said the project would cost “only” 250 million to 450 million dollars (capital/construction costs) and implied that this was for 13,000 af of water. In fact, these figures were taken from the Bureau of Reclamation’s “Value Planning” Study and the 250-450 million figure was for “Phase One” of the project which would divert less than half of the 13,000 af (the rest being lost to evaporation and percolation/seepage) and wouldn’t even get the water out of the Cliff/Gila Valley where there are no buyers for the water due to per acre foot costs. To get the water to Deming would require the completion of “Phase Two” and “Phase Three” and a cost of upwards of a billion dollars, according to the BOR’s “Value Planning" Study.

The Deming City Council signed on to the JPA. The ISC got one of the two urban areas aboard, for the time-being, on the AWSA diversion project. It is not to their credit that they had to fudge the facts and obfuscate and manipulate the public process to get it done.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Squawfish on a Fly

July 30, 2015

Of course they don’t call it a squawfish anymore and it’s just as well it is now the Colorado pike minnow. I give the nod to the new name not out of political correctness but because the creature — pike-like — is long and lean, has a mouthful of long teeth, and gets big; to 50 lbs. and more. I joined, or perhaps created, a fly fishing elite circa year 2000 when I caught three of them on a 10-day, 45-mile, canoe trip down a reach of the Verde River of Arizona. I’d like to catch some more but the odds are against it.

It was circa year 1995 when Arizona Game & Fish (AZ G&F) and the U..S Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS) released some 10,000 fingerling pike minnows into the Verde, part of a recovery effort of the fish as a listed endangered species. Concurrently, the agencies began a control program, mostly using electro-shock treatments, against the non-native predatory sport fish that had long ago invaded the Verde and now were in conflict with natives like the pike minnow. This included smallmouth and largemouth bass, channel and flathead catfish, and carp. By the time our party of canoeists put into the Verde the recovery effort was well along and agency personnel were eager to see the results. At least one of them was most interested to hear that I had caught 3 pike minnows on rod and reel.

“I got one on a wooly worm, one on a pistol pete, and one on a bait casting rig with a live hellgrammite,” I said. “They were about 15 to 18 inches long and felt like an eel on the end of the line.”

He took notes and reminded me to keep all the non-natives while turning all the native fish loose. Well, I sure wasn’t going to keep an endangered species but I didn’t tell him I wasn’t going to keep any fish I didn’t eat, but that’s another story.

Alas, the recovery of the pike minnow is on the ropes. A survey of the Verde about a decade after the initial release turned up fewer than 100 fish, all part of that release and thus no evidence of recruitment. An occasional lunker turns up elsewhere in the Colorado drainage but despite control efforts catfish and bass continue to far outnumber the natives. Controversies continue to haunt native fish recoveries in the West; nobody can say why the pike minnow, a seemingly significant predator in it’s own right, can’t seem to equal the competition……..the answer may go well beyond conflicts with non-native fish. Those of us who have caught a pike minnow will remain scarce as well.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Choose a Few Flies for all Seasons

July 26, 2015

Flies are part of the fun of fly fishing. To some people I think they are even more interesting than the fish or the fishing. I can understand that, to a point, and tying flies has come to be a hobby (or sport) unto itself.

Each fly is different, many are beautiful, like a tiny jewel, some so much so that you almost hate to cast them out there for fear they might be never seen again. And, on the other hand, each is an invitation to fantasy; you can look at an individual fly and wonder what it might catch next time it hits the water.

Still, one can get lost in fly selection; there are so many options. I like flies, especially the pretty ones, but to keep things manageable I put in my fly box a relative few styles that ought to work most anywhere. Here’s my choice for a few flies for all seasons.

First, to cover the possibilities, you need some that sink and some that float; some that imitate and some that attract. And as we’ll see, there may be some overlap at times.

The Wooly Bugger should be in any fly box and of course it’s a sinker. Black ones imitate hellgrammites or leeches, brown ones imitate crawfish, and green ones could well be a bullfrog tadpole to a fish. Dead drift them and they are imitators, but jig them and they become attractors. Use one with a bead head and you can get down deep without a split shot, and I think the bead itself can act as an extra attraction to the fish. They come in all sizes but are famous for enticing the bigger bass or trout. All said, a dandy fly.

Another relatively large fly for larger fish is the Marabou Minnow. It does rather take on a minnow-like movement with a little help from you and they come in colors to imitate most minnows you find in your local waters. But really, I’d say color seldom matters. Fish go for the marabou more as a moving minnow lure rather than precise imitation. All those flowing feathers in flight stimulate fish to strike; it simply works.

Is the Pistol Pete a fly or a lure? It casts like a fly, once you get the hang of it, but that spin propeller makes it a spinner too, as though it belonged to a spinning rod. The spinner works even on a dead drift, but more so when you jig it or simply strip it in. Whatever, it is an attractor fly that comes in all colors, usually on a #6 or #10 hook. Purists won’t use them but, no purist, they sure work for me.

One could name nymphs in the hundreds but who could name a better one than the Prince Nymph? Where the above are all big, attractor-type flies that sink the Prince Nymph is usually on a #12 to #16 hook and is perfect for small trout in small streams (not that big ones won’t hit it). It must be the white wings, that make it appear an emerger, that time and again allow it to out-fish otherwise similar nymphs. I usually try an upstream cast and dead drift, then, if that fails, twitch it back upstream. It works both ways.

Surface (dry) flies always start with the Adams, not flashy at all yet it fools fish precisely because it imitates sufficiently well a variety of mayflies, et al. And by “and others” I mean a great variety as the Adams is the one dry fly that so often works when there is no hatch on. This is often the case on the Gila streams so always have an Adams in your fly box.

To give the same fly some flash, which sometimes works better, use the Parachute Adams. It is simply the bland Adams with a white furl on top to increase visibility, for both you and the fish. I think the well known Royal Wulff works for the same reason and is also a good addition. I regained my interest in dry fly fishing with the Parachute Adams, fishing for rainbows and browns a few years ago on the headwaters if the Little Colorado River of Arizona.

Most trout on most streams are familiar with the caddis fly hatch. The Elk Hair Caddis in the standard tan color is often best though various shades work. Not that you need a hatch. Again, on the Gila streams, a heavy hatch that truly activates a heavy trout rise is unusual. Simply use the elk hair when the trout are hungry, which is most of the time.

The Elk Hair Caddis, Adams, Parachute Adams and Royal Wulff should have you covered for dry flies. There are a couple of others that float that you will also want though they hardly resemble dry flies.

Dave’s Hopper has become a standard grasshopper pattern and as summer wears on hoppers multiply, get bigger, and some of them land in the water. Trout and bass, and others, allow few to escape. When you see live hoppers on the bank assume a Dave’s Hopper will work in the water. Lay it out up-current and watch the drift, at the ready.

Finally, you ought to have a few “popping bugs.” These float, some fish hit them when they land, but the “gurgle” the bug puts on the surface when you pop it is what activates the quarry. These are commonly used to fly fish for panfish but don’t think they won’t work on a calm evening on a local stream for trout or bass.

Well, that’s an easily acquired handful of flies for most anything you might encounter in the streams of New Mexico or Arizona. You’re covered. It doesn’t mean you’ll score every time, but run through this list and catch nothing and the problem is likely something other than the fly!

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Some Horse Races I Have Known

July 12, 2015

Well, American Pharaoh did it; won going away at the Belmont Stakes, taking the extra quarter mile in stride over the Derby and Preakness distances to win the 1 1/2 mile race just 2½ seconds off the track record set by the indomitable Secretariat in 1973. Put another way, to win the Triple Crown of horse racing you need to be an equine who can average nearly 40 mph for three consecutive races from 11/4 to 11/2 miles in length. No wonder no horse had done it in 34 years! Secretariat, American Pharaoh, War Admiral and Seabiscuit ; these are legends of American sport; as great and laudable as Jesse Owens, Michael Jordan, or Larry Bird. For there is something about a horse race. .

And I’ve often thought, to be the jockey, the rider, of one of those major league horses has got to be one of the most physically exhilarating experiences in sport; indeed in all of life! I say that as I’ve been in a few horse races myself.

Mind you, these races were not around a track, nor were they scheduled events and they didn’t involve Thoroughbred or any other high-toned breeding of stock. But even a cow pony can run, fast, and if you’re aboard any thousand pound quadruped at 40 mph you won’t forget it any time soon. I found this out when I was seated on a horse named Red Wing when she took a run at a wild cow called Old Yeller.

I wrote this up in this column a while back but in short, I arrived at a ranch job in south Texas in 1963 (17 years old) not knowing a curb bit from a snaffle but granted the privilege of riding, at different times, every horse in the remuda, from Fino Blanco who was untrustworthy and had a hard trot that would loosen your fillings by the end of the day, to Red Wing, who was muy mancito (very gentle), a smooth traveler who knew cows and could run like the wind.

And so when we emerged from the brush onto an open flat there was the wild cow Old Yeller already in full flight. Red Wing “built right to her” with no urging or direction from me and I simply turned her loose and concentrated on not falling off. And that’s when I learned something about riding a horse at speed — although scary, it’s probably a horse’s smoothest gait.

As Red Wing came up to full gallop, her neck came slowly down and she was reaching out with head and muzzle like she could smell a fresh apple just ahead and with that, at full pace my seat in the saddle smoothed out with the length and ease of her stride. It was a race all right but not a fair one as she soon over-hauled and flanked that maverick cow, allowing the foreman, Mr. Ott, to come up on the other flank and throw a loop. Old Yeller was caught, Mr. Ott earned and got the credit and even I didn’t look too bad, thanks to the horse.

Later, in Minnesota, there was Jesse, my first horse under my ownership. Jesse was a mixed breed paint horse, otherwise nondescript and certainly nothing to match the elegance of my girlfriend’s Arabian gelding with his arched neck, finely chiseled head and muzzle, and short-coupled, muscular frame. One day when the Arab was prancing along on a dirt road in a cold wind, she said, “Let’s turn them loose to the section line road up there,” and the race was on.

Well Jesse might have been of ordinary conformation but she could sure run and she had the Arab by three lengths when we crossed the section road after about a quarter mile run. . . . . . . she split the breeze!. .

The third equine in my horse race memoir, well, I can’t recall his name. But he was a gelding owned by a fine old gentleman, Mr. Albert Hebbert (1905-1999) of Ashby, Nebraska. This was a Sand Hills pony, and Mr. Hebbert said, “He’s a top-notch cow horse and he loves to hunt coyotes.” Well hunting coyotes is what we were to do that day and I knew as I stepped on I was well mounted; he was tremendously alert, eager, and responsive. And Mr. Hebbert was right about his being a hunter; indeed, I’ll just call him “Hunter” for this story.

As we rode out over those remote, wild Sand Hills grasslands with the hounds, Hunter was constantly on the lookout for a coyote. He could see better than the hounds due to his height and he spotted two of the little wolves at very long range before I saw them myself. But they were well out of range. The third coyote that day was close enough for all to see and the race was on!

Now among those who had preceded us in hunting coyotes and jackrabbits on the plains with coursing hounds was General George Armstrong Custer, Theodore Roosevelt, and in New Mexico, naturalist Earnest Thompson Seton, and the cowboy-novelist Max Evans. All I’m sure would agree that the idea is not to race the hounds to the catch (too dangerous) but to use the horse’s mobility to keep sight of the hounds and get a good view the race. But apparently Hunter didn’t think so.

Hunter wanted to go right with the hounds, and when I tried to pull him up he took hold of the bit and went on………….when I tried harder he took to pitching about such as I thought he would throw me. I suppose a better rider would have kept him under better control but rather than getting pitched off I turned him loose……….

My gosh what a race that was, uphill and down, dodging yuccas and jumping soap weeds; and a thousand yards later when the hounds rolled that coyote, I mean I was there! When Mr. Hebbert rode up at a sensible pace I said, “Mr. Hebbert, this is quite a horse you gave me to ride.” And he said, “Oh, he’s a little fiery.”

No, it wasn’t the Belmont Stakes, but it was still quite a ride!

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The Beauties of the Three-Day Camp

Three days makes for a nice campout, especially for the fisherman. Day one is the hike in, with backpacks at their heaviest carrying all the food that will be gone three days hence. But you're fresh and eager and you forge ahead, though weighted down, to a good campsite. A good campsite this time of year means close to good fishing and plenty of shade. If there's time enough you may even cast a fly or bait that first evening, after setting up camp. At the least you will rig up your rod to be ready for manana.

You don't plan to move camp on a three-day camp-out; that's one of the beauties of the schedule. So when you wake up your only concern is breakfast and you're ready to fish. All you need is a day-pack for lunch and camera and you're ready to hike the waters, looking for the better pools and runs. In the evening you return to the old campsite, which is beginning to seem like home only now you've got some fish stories to tell.

Day three you do have to break camp. But, following breakfast, virtually all the food is gone and that backpack feels almost like a day pack when you put it on. So you stop along the way and fish a few of the better spots on the hike out. With any luck you finish with a couple more fish stories to tell.

That's the ideal and here's how it worked for Bud and I just a couple of weeks ago.

We didn't need to pick the hottest, driest time of year but there was a reason for it. Last year we waited for the cooling afternoon clouds of July and waited too long. You may recall last summer the rains came early. They didn't stop till November; the streams ran high and muddy for months. So this year we didn't wait and figured to take the 90-degree heat and clear waters with the three forks of the Gila running about 25 cfs apiece.

We picked one of those forks and we cheated a bit. I always have seven or eight big, leggy hounds and there's no reason one of them can't come along and carry part of the load. So we picked young Archie, trained him to the dog pack, and he carried the cook gear and the apples and oranges. He proved a natural pack dog and I figure took about 6 lbs. off each of our backs. And there's nothing like a good dog to keep the bears and coons out of the camp.

It was a stiff hike upstream and with us loaded down; we worked up a good sweat going in. But we found camp inside of three hours. We set up the tarp and some rolling thunder and lightning bolts kept us there till dinner. But it never did rain much and we got our rods strung up We grilled steaks, boiled some quick brown rice, put out the fire and went to bed.

In the morning I tied on a beadhead prince nymph and gave Bud something called a "crystal nymph." He said it looked like a "Christmas tree ornament." But at the first pool he caught a nice 10-inch bass. At the next pool he caught a bigger one. He has the roll cast down and hooked and lost several other fish, too. I finally got on the board with a 12-inch rainbow. All these fish made our 4-weight rods bow and throb. Then we found "the pool."

This was really a deep run with slower water at the bottom end where author/angler Rex Johnson and I had done real well a month earlier. Bud and I did well here too; he caught a 15-inch bronze bass; I got a 16-inch rainbow and a 12-inch brown.

Bud was out-fishing me but disappointed he couldn't catch a trout. After lunch, just before we turned around to head back to camp, he caught a rainbow near 15 inches. It jumped twice and he was ecstatic and said the rainbow was his "favorite fish." Then he broke his rod tip in the brush and we were down to one rod.

At camp, another false thunderstorm put us under the tarp where we napped. When it blew over I said, "Bud, there's a fair pool just below camp."

There was, but a better one had formed 100 yards downstream since I'd been here last; rivers are always changing. Again it was more of a deep run, with a slow–water pocket at the downstream end. I could just imagine a big bass sitting, and feeding, in that pocket.

He was there! And he took my nymph. But after putting a big hoop in my rod he swam straight to me. I reeled with all I had but was way too slow; right near my feet he surfaced and shook his head and tossed the fly on a slack line. That was a wild, stream smallmouth, big as a lake bass, and this day way too smart for me.

Taking turns with the rod, Bud caught another good bass out of this pool, though not the trophy I lost, and I added another rainbow. It sure was nice to know there was a hole like this right below camp. And back at camp Buddy said, "Dad, there's a rattlesnake right here."

In a brush pile not a stone's throw from where we slept a rattler had his own camp. He was a big diamondback with a thick body coiled to strike, buzzing his tail and too close for my comfort, especially with dumb Archie wandering around ignorant of snakes. My custom is to just leave them alone, but not when they're sharing camp. I confess I planned to kill this rattler and grabbed a stick. But he struck the stick before I could strike him, then went down a hole. We tied Archie to curtail his night wandering -- that's when snakes hunt in the heat of summer – and he stayed with us under the tarp all night. We humans slept with a certain unpleasant alertness but the snake hunted elsewhere, apparently, as we never saw him again.

Our packs were sure enough lighter on the way out. And we caught a couple more fish, leaving Bud, who kept score, with 8 bass and 1 rainbow; me with 1 bass, 1 brown, and 5 rainbows. Archie carried his pack like it wasn't even there, we saw a mother duck with babies, a mother turkey with babies, 2 deer, one black hawk, an angry snake, no other people, 16 fish, all released, and Bud said he didn't even miss his video games.

I am now convinced of it: America's youth needs nothing more than a fly rod, a wilderness, and the beauties of a 3-day camp.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Wild Trout, Fish Poison, and Ted Williams

You know Ted Williams the baseball player; as a hitter, likely the best who ever swung a bat. You may or may not know Ted Williams the scribe, possible the best conservation writer in the business. A fly fisher and bird hunter in his free time, month by month Ted Williams the scribe skewers dirty industries, polluting politicians and other anti-conservation forces and individuals in the pages of Fly Rod & Reel and Audubon Magazine. He usually hits the mark and deserves an even wider audience.

He also misses on occasion, in my humble opinion. Yet this merely makes his writings that much more interesting. Our first debate goes back some 25 years.

The coyote had moved into William's native Massachusetts. Local hunters began calling for a hunting season on this expanding population, but in Gray's Sporting Journal Ted William's thought not. "Why make game out of non-game?" he wrote. As a reader, I responded that hunting coyotes with hounds in the northwoods on snowshoes was perhaps the ultimate in primitive pursuit and physical challenge and left New England grouse hunting looking rather pallid in juxtaposition. Gray's printed my letter and while I doubt I changed Ted's mind it was a fun debate.

Later, in another journal, Williams struck me as oddly unconcerned that animal rights types had used a referendum to ban cougar hunting in California. Cougars were and are extremely plentiful in California and in a letter I suggested not only that they are a legitimate game animal, but that Williams was biased against houndmen. He would respond differently, I said, if grouse hunting were banned in Massachusetts. But the buggers never printed my letter.

Lately, Ted Williams and I have had a go at fish poisons. In the current issue of Fly Rod & Reel he called me out, implying that I was among those who wanted to ban Antimycin (Fintrol) as a piscicide (fish poison) and that I believe that native trout are "good enough if, say, 80 to 90 percent pure."